A Network of Spores

A Network of Spores

Jenna Sutela: You presented the Mycelium Network Society project as part of the Ecologies excursion at transmediale this year. Since you come from a background in digital media and internet-based art, I was wondering what led you to explore such organic networks?

Shu Lea Cheang: My work in all threads—net-based, networked installation, and performance—focuses on constructing and interrupting networks that permit public intervention. The Mycelium Network Society is an initiative I started with Galerija Kapelica in Ljublijana and Stadtwerkstatt in Linz. I have always wanted to bring these two art spaces together and found fungi as a medium.

In Stadtwerkstatt’s information lab, the artist Taro grows the most amazing mushrooms, and Kapelica’s wetlab BioTehna houses artists who work with mycelium and fungi. I have been post-net for some time and my personal work in recent years has been focusing on bio-hacking and viral love. I have made an exit from the net as we know it to scheme a BioNet inside the human body. The Mycelium network is an Earth-bound network extension, born out of the mudlands to divert the pursuit of magic mushrooms from a state of hyper-hallucination to collective fungi consciousness.

As we investigate the fungi culture and its network capacity to communicate and process information, we are interested in constant molecular communication à la mycelium. The ongoing project plans to gather, cultivate, and exhibit artists who work with mycelium as medium. This summer, Stadtwerkstatt’s Eleonore residency, which I have been associated with as an artist and curator, started the Mycelium Network Society residency program with three artists in residence, selected through an open call: Servando Barreiro, Callum Caplan, and Azucena Sanchez. Their residency project development will be showcased at STWST48x3, a 48-hour extravaganza hosted by Stadtwerkstatt, in association with Ars Electronica, to take place in September.

Could you speak more about what the concepts of “hyper-hallucination” and “collective fungi consciousness” mean to you and the network?

Hyper-hallucination responds to the association with magic mushrooms, and collective fungi consciousness asks us to consider mycelium’s network possibilities—from its ever-processing molecular communication to the horizontal branching of self-constructed organic networks, wild and raw, where management fails and intervention prevails.

What sort of projects are developing as a result of the society and the residency?

Servando Barreiro, a Spanish artist, will make a degenerate journey with the Psilocybin mushroom. Mexican artist Azucena Sanchez’s “Byndelle Hybrida” seeks a state of hybrid continuum through the process of mycoremediation and decontamination. Callum Caplan from the UK is building a boat with mycelial material that grows to form the boat’s waterproof shell. Next, we should see how the wind blows the fungal spores. Where will MNS find a moist forest to expand?

You have worked with other foodstuff, too. For example, Location id: HoME (2017) is a speculative cooking/feeding performance. It is set in the year 2030 when food is scarce and the government is producing synthetic, liquid meal replacements for its citizens. The performance is about political resistance through farming. Could you explain how this works?

Many of my food projects involve audience participation to make up science-fiction scenarios and advocate certain issues of concern. Drive BY Dining (2001, Amsterdam) called for public wifi, and Garlic=Rich Air (2002, New York) made garlic a commodity that could be exchanged for public wifi. At that time, the 802.11 wireless spectrum was made available and I was involved with network activists to demand its free public accessibility. As another kind of exchange network, Seeds underground (2013, Linz) hosted underground parties to exchange bio-diversity seeds.

Location ID:HoME further makes up a future scenario—by year 2030, years of cross-breeding by the corporate operative have left vast farmlands barren, since sterile GMO seeds fail to produce any crops. The seeds saved from the biodiversity era have gone underground and are cultivated in tiny hidden plots by the resistance farmers. Meanwhile, the government controls the food supply, piping out synthetic liquid food to “feed the public.” The resistance farmers emerge with mobile kitchens, cooking up a “home” where the deserters of the government food program find their way by tracking the smell and gather to share the food. The project just has its first run at Agrikultura Triennale in Sweden and will be presented as part of STWST48x3 in Linz this September.

Another kind of liquid future is presented in your movie FLUIDØ, which I saw at the Berlinale in February 2017. Here, certain bodily fluids are consumed as a psychoactive drug. Could you talk a bit about this project—particularly in relation to body boundaries and collective experience?

FLUIDØ connects to the body/sex thread in my work. Viruses, sex, drugs, and conspiracy make up the cypherpunk sci-fi movie. Set in the post-AIDS future of 2060, where the Government is the first to declare the era “AIDS FREE,” mutated AIDS viruses give birth to ZERO GENs: humans who have genetically evolved in a very unique way.

These gender-fluid ZERO GENs are bio-drug carriers, and the white fluid they produce is the hypernarcotic for the twenty-first century, taking over the markets of the twentieth-century white-powder high. The ejaculate of these ZERO GEN beings is intoxicating and therefore becomes a new form of sexual commodity. The new drug they produce, code named DELTA, diffuses through skin contact and creates an addictive high.

A new war on drugs begins and the ZERO GENs are declared illegal. The government dispatches drug-resistant replicants for round-up arrest missions. When one of these government android's immunity breaks down and its pleasure centers are activated, the story becomes a tangled multi-thread plot and the ZERO GENs are caught among underground drug lords, glitched super agents, a scheming corporation, and a corrupt government.

We have surrendered our bodies to be colonialized, engineered, reconstituted. The shell of a body contains data that are inaccessible to us. FLUIDØ’s excessive ejaculation reclaims the free flow of body fluid. I want the movie to be watched in the cinema, where an audience can collectively experience the raw, uncensored body power.

Your cyber-organic work brings to my mind an alternative history of cybernetics. Cybernetics is often associated with the idea that biological, social, and physical behavior is fully programmed and reprogrammable. However, the more experimental cyberneticists—like Stafford Beer, for example—always saw the world as ultimately unknowable and thought natural systems, or biocomputers, would be flexible enough to respond to it: "growing solutions to problems" as opposed to computers that are more rigid.

In my own small artistic practice, I build my own system, my platform, my protocol, and my network, which is highly programmed and structured with loopholes to allow public intervention that can be unpredictable and certainly organic. I count the human factor when conceiving an art project. To go for ultimately unknown and natural, I refer to mycelium as ordained by Paul Stamets as “the neurological network of nature.” The Mycelium Network Society as an artist-connecting project may be more of this alternative cybernetic approach. We will see how it grows horizontally and sporadically.

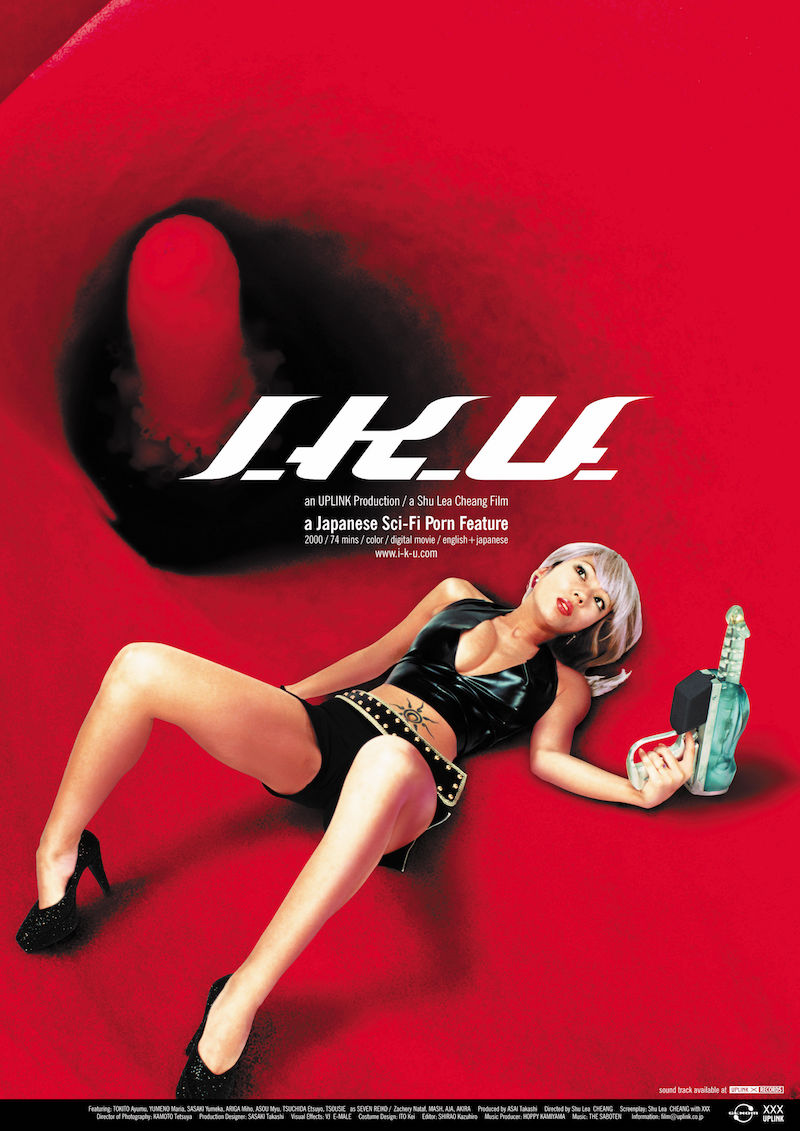

I am also fascinated by the way in which you explore the limits of scientific inquiry by, for example, presenting orgasmic sexual marathons in service of science (the collection of “orgasm data” in the 2000 movie I.K.U.). Do you think fiction plays a role in science at large?

I am in awe of science as I don’t have much access to research fields. Once I claimed myself as a high-tech aboriginal who borrowed technology. Not owning technology in a way is liberating—allowing me to free associate, to jump-start raw and crude concepts that are yet to be legitimized. I am currently developing another sci-fi film, UKI, cinema interrupted, in which the Genom corporation has taken human body hostage to a (post-net) BioNet. I have now gained some access to PRBB (Barcelona Biomedical Research Park) in Barcelona where I can do some research into cell design of a biological system.

This connects back to your ideas on the connections between science and commerce, or orgasms and commerce, as present in FLUIDØ and elsewhere…

In I.K.U. the Genom Corp. dispatches replicant IKU (orgasm) coders to collect human orgasm data, which is downloaded when the coders’ hard-drive body is full with data. Genom Corp. codes the orgasm data onto chips and markets them to be plugged into mobile phones. A spectrum of color-coded orgasms is sold through coin-operated machines located at street corners. Bodies are packages made to open and orgasms are data that can be stored, purchased, and consumed. In FLUIDØ, the act of collective masturbation is orchestrated by druglords to harvest the ZERO GENs’ sensual substance for consumption. Currency exchange is involved in this transaction of pleasure and labor. While the patrons of the fluid drug take in simulated orgasms for viral high, the defunct replicant goes through an orgasmic work-out to reboot her computational body system.

This is some very interesting cyberpunk to me! How did you end up with orgasms and orgasm data as the topic of the film? I’m curious how orgasms relate to the unconscious, or how they are controlled by the involuntary/autonomic nervous system. Did you think about this in relation to (unconscious) technologies—like the replicants, for example?

In my view, orgasm is a very conscious, dedicated endeavor, a hard-earned pleasure that often involves durational, tedious foreplay. The Japanese word for orgasm, iku, actually means “going” rather than “coming.” Upon arriving at orgasm, in Japanese one might call out iku, iku, going, going. Between coming and going, the spark of controlled energy flows both ways. Before Tinder and Grindr, I.K.U. portrayed stored orgasm data on-the-go, ready for download and consumption, a clean transaction sans foreplay. The manufacture of replicants is a corporate business venture to exploit the work force. UKI, as a sequel to I.K.U., pushes further to propose a colonialized body unwired. I have come to terms with loving the replicants, to surrendering my corporeal self for yet another network scheme.