1995: The Year the Future Began, or Multimedia as the Vanishing Point of the Net

1995: The Year the Future Began, or Multimedia as the Vanishing Point of the Net

The Revolution of digital media has only just begun, CDs as data carriers, hundreds of TV channels, interactive information networks with sound and image — the mediascape is definitely becoming more complex and versatile. The demand for digitally created images and image sequences is rising. Are you prepared?

— “Neuland,” advertisement for a German AV company in the catalogue of VideoFest ’95."1

95 was the year of the fall of Techno and the rise of the Computernetworks. “Internet Kills the Raving Star.”

— Geert Lovink and Pit Schultz2

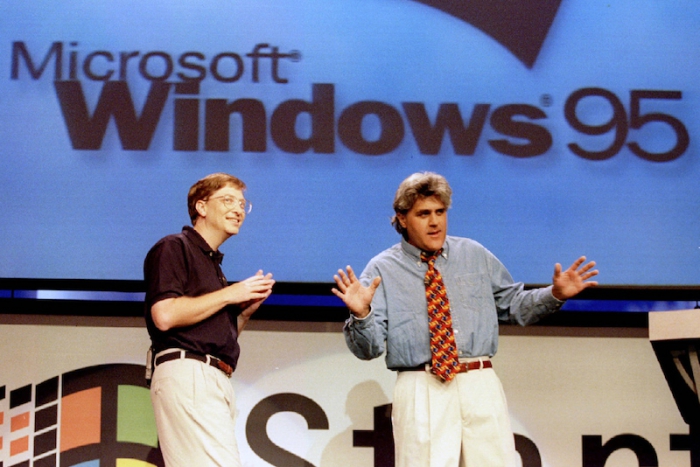

On a rather dubious mission to mark 1995 as the most influential year in recent times, in 2015 the author W. Joseph Campbell launched his book 1995: The Year the Future Began, citing five “epochal” events. These were the mainstreaming of the internet (referring to the popularization of the www, with the browser Netscape joining the stock market and the launch of Microsoft’s multimedia operating system, Windows 95), the O. J. Simpson trial, the Oklahoma City Bombing, the Lewinsky Affair, and the Dayton Agreement peace treaty.[fn]Joseph Campbell, 1995: The Year the Future Began (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015). According to Campbell, these “events” together mark watershed “developments, in new media, domestic terrorism, crime and justice, international diplomacy, and political scandal.”3 There are several problems with this thesis, not least its conflation of longer running technological and political processes, such as the development of networked communication or the Balkan conflicts, into year-defining “events,” and the US-centric idea of an emerging future determined by Northern American domestic and foreign policy (however influential). Yet admittedly there is also something convenient about considering 1995 as a defining point in time for our post-digital condition, not so much because of the continuities with the present age that it proposes (such as the importance of the internet and the emerg ing mainstreaming of digital culture), but for the conflicts and contradictions within digitization that started to appear more fully in that year.

Post-Digital Vanishing Points

Inspired by the idea of the medial “vanishing point” as described by Siegfried Zielinski in his study of the parallel histories of cinema and television, titled Audiovisions, I will here consider the different sociotechnical imaginaries opened up by analyzing 1995 from the point of view of the transmediale festival.4 Although not overtly theorized by Zielinski, the vanishing point as applied throughout Audiovisions becomes a perspective from which to look at the history of cinema and television through their delineation by specific “technical, cultural, and social processes.”5 These processes for Zielinski are, in the case of cinema, related to industrialization in which cinema becomes both a sedation and orientation point in the rush of progress, and, in the case of television, to a post-war demand for an individualized media consumption realized as a mix of mass mediation and living-room intimacy. In his book, Zielinski discusses how these media forms marked vanishing points of large-scale social processes in the way that they were necessary responses to new living conditions. Thus when he, as an unconventional media historian, speaks of the end of cinema or television (or indeed of the concept of media in general), he is not referring to definite ends but to the final stages or transition points of certain time periods contingent with, and therefore delimited by, large-scale social changes such as industrialism. Similarly, when speaking of the notion of the post-digital today, it is not for me a term that denotes the end of the digital, but rather a term that describes how a certain historic mobilization of the digital both as ideal and material has become subsumed in larger socioeconomic and global development schemes, where everything, to some extent, is already digital (and even analog entities are bound up with digital information flows).

The vanishing point of all media might therefore seem to be the totalizing moment of the digital, but it is precisely at this point where the distancing operation of the post-digital concept can open up readings that explore how a medium is always many different things at different points in its history. No history can be written from the totalizing perspective that any specific medium was always tied to a specific development. Instead, I will attempt a transversal analysis by touching down at a specific point in the history of transmediale, which becomes a vanishing point of media art history, able to inspire new modes of thinking and acting in media.

Back to the Future

Returning to 1995 with a more nuanced perspective than that of Campbell, that year also marks a point in time that is very much defined by what Wendy M. Grossman called the “net.wars” in her 1997 book of the same name, which chronicled different struggles between control and freedom in the early days of (inter-)networked mass communication (concentrating on the early to mid-1990s). In those years, many of the digital culture debates that are taking place today on a global scale and in the wider public sphere, through mainstream politics and media outlets, were just being established. These concerned, for example, intellectual property, privacy, data collection, and online social behavior. Such topics were initially discussed mostly within a Euro-American discourse, with a bias toward the US euphoria about the endless transgressive possibilities of our virtual lives in cyberspace, as well as the promises of global entrepreneurial freedom on what the Clinton/Gore administration famously referred to as the “information superhighway.” It would be all too easy, however, to present the 1990s as the years of digital euphoria and the dot-com bust that followed as a shift from utopia to dystopia. More reflective and critical voices on the topic were certainly also there in the mid 1990s, and the most exciting of these were not of a cultural-pessimist kind but came mainly from within an emerging “critical net culture,” for which 1995 was also a watershed year. It was in this year that Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron published their famous critique of the Wired magazine–influenced discourse on digital culture, “The Californian Ideology,” which linked the merging of American counter-culture and neoliberalism to the new digital bohemia of the west coast.6 In a related spirit of anti-Wired-hype, Geert Lovink and Pit Schultz founded the seminal mailing list “nettime,” for “net criticism, collaborative text filtering and cultural politics of the nets.” 7

Videokultur Goes Multimedia

Initially, transmediale was formed in 1987 as a video art festival organized by the Berlin video collective MedienOperative, as an offshoot of the Berlin Film Festival’s “Forum” section for young cinema. The first proper festival was held in 1988 under the name VideoFilmFest, still in cooperation with the Forum, but for the first time also featuring an independently produced and curated program. From the very beginning, its makers understood the festival’s unique role in providing a space between established film genres and modes of production, and also opened up the narrow focus of film festivals to also include art and new media work that did not necessarily take place in the cinema. On one hand, VideoFest (so named in 1989) wanted to be an agent provocateur, presenting new types of art practice through media. On the other hand, it aimed to cast these new practices in a realistic light, not succumbing to technological hype but staying open to the possibilities of technological change while critically discussing its pros and cons with regard to artistic production.8 By the early 2000s, transmediale had become a natural meeting point for these discussions (under the leadership of its second artistic director, Andreas Broeckmann), but in 1995 VideoFest only cautiously embraced European critical net culture. For a festival still mainly rooted in independent and artistic Videokultur but with ambitions to expand to a wider inclusion of new media, the 1995 edition must have presented the organizers with some dilemmas — at least this is the impression one gets when reviewing the program, which contains a number of interesting contradictions. In 1994 VideoFest was among the first to feature the pioneering German net art project Handshake by Karl Heinz Jeron and Michel Blank.9 Named after a communication protocol, the approach of this artwork was typical of the time, as it foregrounded the infra structure and act of networked communication rather than its representational content and formal aesthetics. Maybe this is why, in 1995, as the early hype about the internet and the web was reaching its peak, VideoFest chose to almost reverse its approach to the internet, offering only one out of four installed exhibition computers with an internet connection, keeping the rest offline. According to the catalogue statement explaining this decision, networked communication was seen as incompatible with an in-depth experience of art: “the emphasis of this year’s VideoFest is on exhibiting exciting works (like paintings in a gallery); we already offered you opportunities to explore the net and to surf in it last year.”10

While one of the focus points of the 1995 festival was “multimedia,” divided into CD-ROM–based and internet-based works, the open-ended character of the use of the latter medium was apparently subordinated to an idea of a museum-like reception. The irony was that the offline form of presentation ended up being even less museum- or gallery-like, as it foregrounded an individual rather than a collective reception of the artwork (which at least is manifested in an online presentation). This idea of multimedia was arguably informed mainly by home computer, specifically gaming culture, as that was likely to have been the most common point of contact with digital interactive environments for the general audience at the time (as well as for the curators and artists). In his introduction to a panel on Multimedia, Micky Kwella, the artistic director of the VideoFest, reinforced this thesis by somewhat negatively stating that the new medium was dominated by games and porn and that the mission of the VideoFest focus on multimedia was to provide a grounded counterpoint to the hype, to show the artistic limitations as well as possibilities of multimedia and internet art.11

"Reactionary Pigs!"

There was, in other words, an anti-consumerist streak in the approach to multimedia, which was arguably characteristic of VideoFest as a whole regarding alternative media culture. In 1994, the festival organizers sent out a questionnaire to the artist-run mailing list “luxlogis” with a series of questions on “electronic culture,” asking recipients if and how various aspects of electronic media could actually be culture, including television and video as well as multimedia. This approach was violently rejected by the Dutch media theorist and activist Geert Lovink, who accused the VideoFest of trying to apply a German brand of cultural conservatism to an open culture of experimenting between media forms.

From: Geert Lovink

Subject: Re: HANDSHAKE — VideoFest94, Berlin

To: luxlogis@uropax.contrib.de (Lux Logis e.V.)

Date: Wed, 2 Feb 1994 08:04:21 +0100 (MET)

Is Handshake culture....?!? Is Berlin Culture.....!?

Don’t spread German self-hate towards media!

Attack all expressions of media-ecology

It is depressing to read as the very first question on your list whether television is “culture.” Television is a technology, a medium as you wish. Although in decline as a one-way, two channel mass medium with huge influence on the population, it’s slowly growing in other directions. People and groups can influence the direction of their own television culture, by starting experiments, doing piracy, working on the connection between television, telephone and computer, by commenting the current narrow ideas of interactivity. And by making television themselves. And not starting to debate such silly topics, dictated by some elitist frustrated German intellectuals who don’t know anything about the media or new technologies and who want to go back to the real world, opera, nature etc. You reactionary pigs!12

This aggressive reaction from Lovink points us to possible contradictions within shifting “electronic culture” as video festivals tried to adapt their cultural classification systems while activists and artists were already thinking beyond ideas of genres of cultures informed by the networked media environment. The VideoFest approach, however, was probably not an expression of cultural conservatism as Lovink here assumes, but rather followed the spirit of Gegenöffentlichkeit, in which the main concern is to create other forms of (often grassroots) participation in culture rather than through commercial or high culture.13 If the festival’s idea of Videokultur was very much defined as an artistic counter-position to mainstream cinema and television, then the initial VideoFest approach to art in emerging digital culture seems formed in dialogue with the commercial game and home computing culture, while only cautiously embracing open-ended flow of communication online.14 This is evident in the 1995 catalogue foreword by Kwella, which states that in the 1970s multimedia meant “an integration of different arts in a live performance,” but has now migrated to an isolated setting of “A sits in front of the computer, immersed in a CD-ROM or surfing through the INTERNET,” where all media forms are still mixed, albeit without the live performance element and “loaded into the computer at home and used right there.”15 This decentralization of access to art by its entering into a digital communication space was seen as positive by the festival, while the commercial use of multimedia was to be “treated as a topic inviting critical discussion.”16 The open, constant flow of information was an element of distraction rather than of empowerment.

CD-Roms after Snowden

With historical hindsight we now know that CD-ROM art and internet art (in its early net.art form) never became established art genres in the way that the VideoFest makers might have hoped for. The formats quickly lost ground to processes of technological obsolescence and the simultaneous expansion and commodification of the social uses of the www (read Web 2.0 and the subsequent dominance of Silicon Valley–developed platforms). When seen from the point of view of linear media history, the web was to be the vanishing point for the relatively short-lived idea of multimedia as based on the offline single-viewer experience at home. This development is similar to how 1970s utopian visions about the self-empowering possibilities of television and video gradually gave way to a standardization of production and distribution based on commercial models.17 However, just as there are legacies of experimental and alternative video practices that continue to be rich sources of inspiration for artists today, there are aspects of multimedia practices of the 1990s that are ripe for rediscovery. Recent reappraisals of CD-ROM art have highlighted their unconventional approaches to narrative, graphic, and interface design, their intimate distribution models, and their importance for the development of both internet-based art forms and the independent games movement.18 In 2015, when the digital culture journalist Marie Lechner asked artists and theorists involved in CD-ROMs what made this art form specific, Antoine Schmitt highlighted that CD-ROM art “opened a questioning on the active relationships between humans and their environment in general.”19 Seemingly contradictorily, Geert Lovink maintained that the most significant features of early home multimedia is that it was indeed happening mostly offline and that therefore CD-ROMs were “NOT social.”20 At the same time, these aspects of CD-ROM art’s opening up and existing offline could be seen to work effectively together, as the “active relationship” Schmitt referred to was, in this case, not foreclosed by the corporate web with its streaming and data-mining models. Instead, it held the potential for a speculative approach, where, according to artist Suzanne Treister, “user generated content was in the mind of the viewer, for them to take away with them, rather than input back into the work.”21

In the current streaming model of cultural content, this (non-)contradiction, of course, makes CD-ROMs seem more than archaic and also vehemently noncommercial. If we look to the game business as that which has carried the cinematic interactive experiences often found on CD-ROMs further, the main trend for years has been toward online multiplayer games. The offline single-player game is not only becoming near extinct in the mainstream, but also increasingly stigmatized as an anti-social form. From a critical post-digital perspective, the single viewing and offline experience is actually where CD-ROMs are relevant as a cultural form that goes against the norm of always being online, with its implications of database structures ready for commercially motivated mining and surveillance. The relevance of going at least partially offline has been demonstrated by the post-Snowden activists and artists, who revisit analog forms of communication as well as hybrid and mesh networking projects to create local infrastructures of exchange, in order to restrict communication to local or translocal communities.22 Furthermore, the so called “notgames” movement of exploratory games such as Gone Home (2013–16) or Dear Esther (2012), and the interactive fiction put out by the DIY community surrounding the open-source tool, Twine, are examples of how the experimental approach to multimedia in the 1990s is being taken up by new generations. The way that VideoFest 95 championed offline and CD-ROM-based multimedia then only becomes ridiculous from a perspective of linear media history, where those forms became obsolete in the wake of the “total” web. If we turn this view around, we can see that the web is not the vanishing point of multimedia, but that multimedia can be seen as a vanishing point of what net culture could have been: anti-consumerist, playfully user-unfriendly, selectively online, and a vehicle for thought-provoking forms of narrative and interaction. The 1995 multimedia infrastructure, then, with its intermittent net access, downloading just what it needed as an internetworked “thing,” shows us the vanishing point of today’s total access and user transparency — and thus constitutes an alternate deep web of the recent history of digital culture.

Techno-Social Imaginaries and transmediale

Media and technological change are notoriously elusive objects of study. Media research, as well as artistic media practice, seem cursed to be constantly moving on to the next thing. “All media are partly real and partly imagined,” as Eric Kluitenberg has asserted, riffing on Benedict Anderson’s influential concept of “imagined communities,” indicating that the notion of the imaginary can help us to come to terms with the elusiveness of media and better understand how the sociocultural meets the technical.23 As I’ve argued elsewhere, the imaginary is a tool for transversal and archaeological media analysis that allows us to capture a certain sense of the limits of a medium, and at the same time to picture how it could be different.24 Due to their operation at the intersection of art, society, science, and technology, festivals such as Ars Electronica, Future Everything, and transmediale feature strong imaginaries of what media are, and what they can and will do in the future. In the previous section, I explained how a specific medial situation related to transmediale history can also serve as the starting point for outlining alternatives to present medial configurations. The historical context of 1995 was that of a “vanishing point,” in the sense that it marked a transition moment where the mediascape was taking on a new configuration: as the name shift from VideoFest to transmediale during the second half of the 1990s indicates, convergent media forms eventually became the norm rather than the exception, leading us not only to the convergent but to the elusive character of media in digital society. Paradoxically, it is only in the post-digital condition that we may now perform a less linear reading of these developments, reinterpreting 1995 as a vanishing point, since both our analog and digital infrastructures have been revealed to be inescapably intertwined on global, geopolitical, and geophysical levels.

Post-Digitality, or the Becoming-Island of Media

Between the media of video and television, there exists a long-established dialectic of the individual and the mass, of participation and passivity, of emancipation and submission, of the DIY amateur and the high-tech professional. Could it be that the multimedia home PC and the internet have held a similar, if widely unacknowledged cultural dialectic?25 Over the years, video art has been heralded as a DIY and participatory medium for personal and intimate expression, which stands in opposition to the professionalized production and mass consumption of television. In contrast to this, digital networks imply a reverse situation, where the harnessing of user content — what, in the television age, might have been akin to home videos ridiculed on shows like America’s Funniest Home Videos — has become central. As I mentioned above, and as Clemens Apprich and Ned Rossiter assert elsewhere in this volume, participation and connection have become compulsive to the extent that going offline is now a privilege and may even become a necessity to protect critical infrastructures in the post-digital. If, in the television age, networks were primarily broadcasting content that was often seen as the opium for the masses, in the internet age the distributed network and its participative feedback paradigm has become hegemonic, completely reversing the marginal position once held by decentralized production, while rerouting models of distribution around new centralities (read the big five: Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple). In this new economy of cultural production, no human can afford to be an island — and nonhumans can’t either, as the Internet of Things promises the ubiquity of information through connecting all (un-)living things. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that a certain “island romanticism” has resurged in the post-digital condition on a wide-ranging scale, from existing geographic islands that mobilize imaginaries (and also economies, after Brexit and offshoring scandals) of populations to the more metaphorical becoming-island inherent to the return to analog and offline media forms that promise a chance to disconnect from the command of incessant information flows.26

In the framework of media art and research, with its focus on technological development and artists as agents of innovation, how shall we critically account for the way that artists are consistently appropriating older technological forms? The fact that artists were early to both push the development and adopt the use of new technologies is a fact with deep historical roots. The way this history is portrayed in mainstream, contemporary accounts of art and technology, however, tends to be reductive, as artists are often either seen as the avant-garde that predict changes or as the critical force revealing the “truth” behind illusory representations of media. If we follow Zielinski’s thesis in Audiovisions, the rise of mass media and electronic means of communication in the twentieth century can be seen as responses to different stages of industrialism, which continue to overlap and contradict each other. This in turn allows us to look at the hyperconnected condition of the twenty-first century as a response to accelerated capitalism. What is needed in the post-digital age is a thorough reflection on the contradictions within societal and political environments in which specific technologies and artistic practices are situated. The transversal discipline of media archaeology and its diverse thinkers such as Wolfgang Ernst, Siegfried Zielinski, and Jussi Parikka have offered rich perspectives on how media history can be read against the grain as a constant hybridization of old and new. They point out how the materiality of media is inscribed within geophysical contexts and temporalities as much as within anthropocentric history. Writing this article in the context of transmediale, it has become clear to me that, although media archaeology has dealt explicitly with artists and artworks, it has not engaged fully with the interaction of artists and institutional milieus (see Parikka in this volume for an exception found in the format of the lab).

Ever Elusive

In a book called Bandbreite, published as a tribute to the first festival director, Micky Kwella, who co-founded transmediale as VideoFilmFest in 1988, the curator Rudolf Frieling wrote that from the beginning the festival was inscribed in a permanent process of transformation that ran parallel to the constantly changing media contents and forms around which it revolved.27 In the same year, the media art historian Dieter Daniels wrote that, compared to similar festivals, transmediale managed to survive for such a relatively long time precisely because it was constantly reinventing itself. Daniels’ argument echoed that of Frieling when he wrote that “the speed of innovation of media and technology prescribes the domain that is today generally known as media art to a permanent state of change of the whole medial context — from television to radio and further to the internet.”28 Instead of sticking with video, a medium that at its origins sat between all chairs, not wanting to be television, cinema, or an art market commodity, VideoFest reformed itself along with changes in the mediascape during the 1990s when “new media” (meaning mostly multimedia and the internet) were increasingly integrated into the festival program.29

When writing now, in 2016, about the soon thirty-year-old festival of transmediale, it is tempting to repeat the narrative of permanent renewal happening in tandem with technological change. This narrative, besides being a bit self-congratulatory, risks reinforcing the pervasive narrative of linear technological progress, which I would argue that transmediale has always, in different ways, formed a critical counterpoint to. It is also problematic in the present post-digital condition, in which technological and social transitions that were formerly taken for granted as indications of linear progress, are once again rendered elusive and seem to be reconfigured in new symbiotic relationships. Nonetheless, it would be revisionist to claim that transmediale did not indeed evolve alongside changing sociotechnical situations in a fairly straightforward way, from video art and the ideals of a 1970s and 1980s culture of Gegenöffentlichkeit to the experiments with interactive multimedia; from installations in the 1990s to net and software art and critical network culture in the late 1990s; and finally to the mainstreaming of digital culture in the latter half of the first decade of the twenty-first century. Instead of looking back in order to arrive at the present as a logical conclusion of what came before, in my analysis of 1995 and transmediale’s approach to multimedia in that year, I suggest a transversal recollection of moments of transmediale history that reorients what we take for granted in present media culture. From this reading, we might reconsider the example of the offline art form of the CD-ROM, not with a nostalgic longing for a secluded and immersive experience of “old new media,” but as a blueprint for a non-streaming economy-compliant mode of producing and distributing artworks, as well as a non-template-culture idea of interaction design. The elusiveness of the present with its retromanias, its postisms, and its accelerationisms is one where past, present, and future are not structured by linear causalities, but rather foreclosed by cybernetic feedback loops and digital capitalism.31 What I suggest here is that an effective response from media practitioners in this situation can be to approach contemporary media practice anew, not by trying to outrun these systems, but by infusing the past with post-digital imaginaries that work to manifest tangible yet non-predictable presents.

You can buy a print copy of across & beyond here.

- 1. VideoFest ’95 (Berlin: Mediopolis e.V., 1995), 43. Translated from the German by the author.

- 2. Geert Lovink and Pit Schultz, “The Future Sound of Cyberspace” in Jugendjahre der Netzkritik Essays zu Web 1.0 (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2010), 63–64. Translated from the German by the author.

- 3. Joseph Campbell, “FAQs About 1995,” The 1995 Blog: The Year the Future Began (2015), https://1995blog.com/faqs-about-1995/ .

- 4. Siegfried Zielinski, Audiovision : Cinema and Television as Entr’Actes in History (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999), 14–15.

- 5. Ibid., 11.

- 6. Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Mute 1, no. 3 (1995).

- 7. http://nettime.org.

- 8. This approach becomes evident in reviewing the program statements by the festival co-directors Micky Kwella and Hartmut Horst, as well as the opening speeches and event documentation from the early VideoFest, years 1988–1995. transmediale physical archive, accessed 2016.

- 9. As was pointed out to me by the curator Inke Arns, Handshake was first shown in 1993 at the Ostranenie First International Video Festival, Bauhaus Dessau.

- 10. “Austellung/Exhibition,” VideoFest ’95 (Berlin: Mediopolis e.V., 1995), 16.

- 11. Festival documentation video, transmediale physical archive, accessed 2016.

- 12. Geert Lovink, “Re: HANDSHAKE – VideoFest ’94, Berlin,” blankjeron.com (1994), http://blankjeron.com/sero/Handshake Feldreise/D/videofest/videofest_antworten.html. Originally sent as an email message on February 2, 1994 to luxlogis@uropax.contrib.de (Lux Logis e.V.).

- 13. Not to be confused with Michael Warner’s later work on “Counterpublics,” the term Gegenöffentlichkeit rose to popularity in Germany during the 1960s and 1970s, not the least through the work of Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt in their seminal Public Sphere and Experience: Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere, first published as Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung: Zur Organisationsanalyse von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1972). VideoFest was originally organized by the organization MedienOperative e.V., founded in the late 1970s, which, similarly to many other German video workshops at the time, advocated video as a grassroots art form for producing Gegenöffentlichkeit through media.

- 14. In contrast to this turning away from online forms, there was an online presentation and communication forum of the VideoFest ’95 that went under the name “Videoweb.”

- 15. Micky Kwella, “Vorwort,” VideoFest ’95 (Berlin: Mediopolis e.V., 1995), 13.

- 16. Ibid.

- 17. For a detailed account of the German history of the relationship between television and video, see Kay Hoffmann, Am Ende Video – Video am Ende? Aspekte der Elektronisierung der Spielfilmproduktion (Berlin: sigma, 1990).

- 18. See Sandra Fauconnier, “The CD-ROM Cabinet after 6 months…” AAAN.NET (2013), http://aaaan.net/the-cd-rom-cabinet-after-6-months/ . See also Marie Lechner “Welcome to the Future! 2. New Art Forms,” imal Center for Digital Cultures and Technology (2015), http://www.imal.org/en/page/welcome-future-2-new-art-forms/ .

- 19. Marie Lechner, interview with Antoine Schmitt, “Welcome to the Future Interview: Antoine Schmitt,” imal Center for Digital Cultures and Technology (2015), http://www.imal.org/en/wttf/texts/interview-antoine-schmitt/ .

- 20. Geert Lovink says: “What makes cd-roms so unique is also its greatest weakness: it is a closed environment, a data monade. The best cd-roms are still more complex than the internet today,20 years later, in particular if you look at it from the average user perspective who is encapsulated into the limited template culture of the dominant social media platforms. Needless to say, cd-roms were NOT social.” Marie Lechner, interview with Geert Lovink, “Welcome to the Future Interview: Geert Lovink,” imal Center for Digital Cultures and Technology (2015), http://www.imal.org/en/wttf/texts/geert-lovink-interview/ .

- 21. Treister also states: “An art cd-rom could not store user data as it is a burnt disc. ROM stands for Read Only Memory.” Marie Lechner, interview with Suzanne Treister, “Welcome to the Future Interview: Suzanne Treister,” imal Center for Digital Cultures and Technology (2015), http://www.imal.org/en/wttf/texts/Suzanne-Treister-Rosalind-Brodsky/ .

- 22. Daphne Dragona, “From community networks to off-the-cloud toolkits art and DIY networking,” lecture, Hybrid City Conference III: Data to the People, Athens URIAC, September 18, 2015; Panayotis Antoniadis and Ileana Apostol, “The Right(s) to the Hybrid City and the Role of DIY Networking,” The Journal of Community Informatics 10, no. 3 (2014).

- 23. Eric Kluitenberg, “The New Cultural Politics of Difference” in Book of Imaginary Media: Excavating the Dream of the Ultimate Communication Medium, ed. Eric Kluitenberg (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2006), 8. For an exploration of Anderson’s idea in relation to the imagined aspect of communication networks, see Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “Networks NOW: Belated Too Early,” in Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design, eds. David M. Berry and Michael Dieter (London: Palgrave McMillan, 2015), 289–315.

- 24. Kristoffer Gansing, “The Transversal Generic: Media-Archaeology and Network Culture,” The Fibreculture Journal, no. 18 (2011); Kristoffer Gansing, Transversal Media Practices: Media Archaeology, Art and Technological Development (Malmö: Malmö University Press, 2013).

- 25. As an artistic medium, video had a long, troubled relationship to television, as the two were often conflated in the 1960s and many “video artists” were either aspiring to be or doubling as television artists. Sometimes this was due to a conflation of video with television simply because of the electronic monitor-based presentation, but also because of a hybrid situation where broadcast television was among the first distribution channels for video art and more generally for video-based production. In 1970, however, Gene Youngblood wrote: “It is essential to remember that VT is not television: videotape is not television though it is processed through the same system.” By the late 1970s it seems as if the art world had also taken up on this distinction, as video art was increasingly institutionalized as an art form separate from television, evident by the presence of a “VT ≠/ TV” sign quoting Youngblood at documenta 6 in 1977, and the emerging theorization of video as a medium set apart from television. Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1970), 281; Kathy Rae Huffman, “Video Art: What’s TV Got To Do with It?” in Illuminating Video: An Essential Guide to Video Art, eds. David Hall and Sally Jo Fifer (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1990), 81–90.

- 26. See Florian Cramer’s article “What is ‘Post-digital?’” for a critical reconsideration of the retrotendencies of young art practitioners who might not have grown up with analog techniques in design, photography, and film in the first place. Florian Cramer, “What Is ‘Post-digital’?,” in A Peer-Reviewed Journal About 3, no. 1 (Aarhus: Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, in collaboration with transmediale/reSource, 2014), http://www.aprja.net/?p=1318/ .

- 27. Rudolf Frieling, “1989 und 2000: Wendepunkte eines Medienfestivals” in Bandbreite Medien zwischen Kunst und Politik, eds. Andreas Broeckmann and Rudolf Frieling (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2004), 141–149.

- 28. Dieter Daniels, “transmediale,” Kulturstiftung des Bundes, no. 3 (2004), 32. Translation from the German by the author.

- 29. Ibid. 31 A similar argument was recently put forward by Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik with the notion of the “post- contemporary,” through which they wish to discuss how, in the current stage of neoliberalism, the present is preconditioned by the future. In their conception this is a future produced from probabilistic models that structure financial and increasingly sociocultural systems of interaction. Echoing the work of accelerationists like Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, they go on to argue that the urgent task today becomes engaging in new production in ways that take non-representational systems into account. My argument here, however, is that such a seemingly oppressive temporal system does not have to be responded to in a way that follows the internal logic of the system, but rather that the systems of neoliberalism and digital capitalism can also be thwarted by producing post-digital counter-imaginaries that establish other temporal orders. See Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik, “The Time-Complex. Postcontemporary: A Conversation between Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik,” DIS Magazine (August 2016), http://dismagazine.com/discussion/81924/the-time-complex-postcontemporary/ .